By Jack Guerino, iBerkshires Staff

Friday, March 31, 2017

ADAMS, Mass. — The Adams BagShare Project is not only making waves in town but across the region and the country.

Town Administrator Tony Mazzucco held a small meeting at Town Hall on Thursday to mark the first day of the town's plastic bag ban and to thank those involved in the project charged with creating 8,400 reusable grocery bags out of recycled material – one for each resident.

"It is a positive step for Adams sand the Berkshire as we continue to make our communities more sustainable … We are moving the town to a green future," Mazzucco said.

"Adams is emerging as a shining star now that we have partnered with the BagShare Project."

|

| A bag of the recycled bags is currently at town hall for residents to take. |

Mazzucco added that the project has grown beyond the town and groups throughout Western Mass are now participating such as Deerfield Academy and Northampton High School's Environmental Club.

He said news of the project has been printed in publications in Hartford, Conn., Portland, Maine, and even on SFGate.com, website of the San Francisco Chronicle.

"They are publishing what we are doing in Adams in San Francisco, which is a win for the community," Mazzucco said. "It’s further proof that the small town of Adams nestled at the base of Mount Greylock is letting the world know what we are doing to be sustainable."

The project began last year sometime after the annual town meeting passed bylaw banning the use of plastic shopping bags. The town partnered with Old Stone Mill owners Leni Fried and Mike Augspurger, who initiated the project in which plastic woven feed bags are combined with irrigation or maple syrup tubing to create tough, reusable shopping bags.

Mazzucco said businesses, schools, civic groups, and other organizations from throughout the region have each committed to making 120 bags. Big Y, the Williamstown Girl Scouts, the Youth Center, ProAdams, Bishop West Real Estate and even Town Hall have all signed up.

He said currently the groups have committed to 3,000 bags.

"Each bag we create keeps 33 plastic grocery bags out of a landfill and with these bags, all of the materials are completely sustainable and the materials otherwise too would be in a landfill ... 120 bags total 39,000 plastic grocery bags and to date, with the commitment we have it is the equivalent of keeping 114,000 out of the landfill," he said.

Mazzucco said this number will more than double by Earth Day if they can hit the 8,400 mark.

Fried said 40 more groups are needed if they want to hit that mark or

groups need to commit to more. She said the group Fillbo Baggins from

River Hill Pottery have committed to 360 bags – three times the original

pledge amount.

Also, anyone can stop at the Fire House Café on Park Street and make a

bag on the weekend. Drop-ins, also known as "Sand Baggers," are welcome.

Adams residents can pick up a bag at Town Hall, where there is a

currently a cache of the recycled bags that will be replenished as more

are made.

Naila Moreira: Plastic bag ban in Northampton ‘necessary, but not sufficient’

- JERREY ROBERTS

Leni Fried, front, of Cummington, who is the founder of Bagshare, uses a grommet press to make a reusable shopping bag from a malt bag as Diane Drohan, left, and Heather King watch Tuesday at Northampton Survival Center. Drohan is the center's volunteer coordinator. King is a frequent volunteer at the center who lives in Florence. Purchase photo reprints »

NORTHAMPTON — A friend of mine recently forgot his reusable bags when he dropped in at Stop & Shop. To make matters worse, he’d also forgotten about Northampton’s new plastic bag ban, which started Jan. 1.

Then the person in line behind him lectured him on the merits of the ban.

“Don’t give me that,” he sputtered to me later. “Paper bags can be just as bad for the environment.”

I favor the ban, but I heard him out. Paper bags, he said, cost more energy and greenhouse gas to make. They consume trees. They’re not as strong, especially if you have to walk a long distance, as many people who don’t own a vehicle must do.

And, he claimed, plastic bags are just as recyclable.

“What’s better, to drive and get a paper bag, or walk and get a plastic one?” he asked.

His arguments stumped me, so I decided to do some poking around. My friend’s a smart guy, so I wasn’t surprised to find him right in some aspects.

Paper bags are no slouch when it comes to environmental harm. Over the whole process of manufacturing, new paper bags require about three times more energy than plastic bags. They therefore emit more climate-change culprits like carbon dioxide. They also require toxic chemicals during paper milling. Moreover, if they’re landfilled, they are unlikely to biodegrade, since no oxygen, water or light is available to break them down deep under the ground.

But that doesn’t give plastic a get-out-of-jail free card.

Plastic bags tend, first of all, to blow away from landfills and get into gutters, streams and oceans. Not only unsightly, they are ingested by aquatic and marine life and even by livestock, clogging their digestive systems. Because they’re made from petrochemicals – oil – they contain toxins that can poison animals and humans. Unlike paper, they don’t biodegrade, even above the ground. Ever. Light exposure breaks them into tiny particles, but those particles are still plastic and just as toxic, if not more so.

Plastic rarely recycled

And perhaps most importantly, although plastic bags can be recycled, they usually are not. Only 0.6 percent of plastic bags were recycled in 2005, compared to 21 percent of paper bags, according to EPA statistics. And that number may be dropping even further.

“Frankly, they don’t have a lot of value, especially right now because petroleum prices have gone down so far,” said Susan Waite, Northampton’s recycling and solid waste coordinator. With petroleum at $30 a barrel, compared with $120 two years ago, “It becomes very cheap to produce virgin plastic, and the incentive to recycle is very poor.” Not only that, Waite points out, but plastic bags gum up most conventional recycling equipment.

“They clog and choke and wind around the machinery. You can go on tours and see the mess that they make,” she told me. “There’s plastic bags wrapped around all sorts of things.” Communities across the country have been moving toward bans on plastic. Over 100 counties and municipalities have bans or fees on plastic bags, and the state of California prohibits them.

In Greenfield, voters in a November referendum opted to keep plastic bags, but to ban plastic foam containers used by restaurants for take-out and beverages. Such efforts take aim at our love affair with all plastic, which consumes an estimated 6 percent of global oil resources. Globally, more than 100 million plastic bags are used each year. And by 2050, plastic trash is on track to represent more mass in the oceans than all the world’s fish combined, according to the World Economic Forum.

I asked Northampton at-large City Councilor Jesse Adams, who wrote the bag-ban ordinance, why he and his colleagues had focused on plastic, without a fee or ban on paper bags.

“Banning both paper and plastic would put a great burden on businesses in Northampton,” he said. “To do away with bags entirely, I don’t know if we’re ready for that.” For myself, I’ve concluded that the plastic bag ban is one step toward environmental sustainability. But, to borrow a phrase from my mathematician friends, it’s “necessary, but not sufficient.”

BagShare program

One cause for optimism could be found at the Northampton Survival Center on a recent Tuesday afternoon. There, a gaggle of volunteers bent over voluminous white canvas malt bags from Williamsburg brewery Opa Opa. Large enough for a sack race, the bags are normally thrown out by Opa Opa at the rate of 300 a week, said Cummington artist Leni Fried.

Then the person in line behind him lectured him on the merits of the ban.

“Don’t give me that,” he sputtered to me later. “Paper bags can be just as bad for the environment.”

I favor the ban, but I heard him out. Paper bags, he said, cost more energy and greenhouse gas to make. They consume trees. They’re not as strong, especially if you have to walk a long distance, as many people who don’t own a vehicle must do.

And, he claimed, plastic bags are just as recyclable.

“What’s better, to drive and get a paper bag, or walk and get a plastic one?” he asked.

His arguments stumped me, so I decided to do some poking around. My friend’s a smart guy, so I wasn’t surprised to find him right in some aspects.

Paper bags are no slouch when it comes to environmental harm. Over the whole process of manufacturing, new paper bags require about three times more energy than plastic bags. They therefore emit more climate-change culprits like carbon dioxide. They also require toxic chemicals during paper milling. Moreover, if they’re landfilled, they are unlikely to biodegrade, since no oxygen, water or light is available to break them down deep under the ground.

But that doesn’t give plastic a get-out-of-jail free card.

Plastic bags tend, first of all, to blow away from landfills and get into gutters, streams and oceans. Not only unsightly, they are ingested by aquatic and marine life and even by livestock, clogging their digestive systems. Because they’re made from petrochemicals – oil – they contain toxins that can poison animals and humans. Unlike paper, they don’t biodegrade, even above the ground. Ever. Light exposure breaks them into tiny particles, but those particles are still plastic and just as toxic, if not more so.

Plastic rarely recycled

And perhaps most importantly, although plastic bags can be recycled, they usually are not. Only 0.6 percent of plastic bags were recycled in 2005, compared to 21 percent of paper bags, according to EPA statistics. And that number may be dropping even further.

“Frankly, they don’t have a lot of value, especially right now because petroleum prices have gone down so far,” said Susan Waite, Northampton’s recycling and solid waste coordinator. With petroleum at $30 a barrel, compared with $120 two years ago, “It becomes very cheap to produce virgin plastic, and the incentive to recycle is very poor.” Not only that, Waite points out, but plastic bags gum up most conventional recycling equipment.

“They clog and choke and wind around the machinery. You can go on tours and see the mess that they make,” she told me. “There’s plastic bags wrapped around all sorts of things.” Communities across the country have been moving toward bans on plastic. Over 100 counties and municipalities have bans or fees on plastic bags, and the state of California prohibits them.

In Greenfield, voters in a November referendum opted to keep plastic bags, but to ban plastic foam containers used by restaurants for take-out and beverages. Such efforts take aim at our love affair with all plastic, which consumes an estimated 6 percent of global oil resources. Globally, more than 100 million plastic bags are used each year. And by 2050, plastic trash is on track to represent more mass in the oceans than all the world’s fish combined, according to the World Economic Forum.

I asked Northampton at-large City Councilor Jesse Adams, who wrote the bag-ban ordinance, why he and his colleagues had focused on plastic, without a fee or ban on paper bags.

“Banning both paper and plastic would put a great burden on businesses in Northampton,” he said. “To do away with bags entirely, I don’t know if we’re ready for that.” For myself, I’ve concluded that the plastic bag ban is one step toward environmental sustainability. But, to borrow a phrase from my mathematician friends, it’s “necessary, but not sufficient.”

BagShare program

One cause for optimism could be found at the Northampton Survival Center on a recent Tuesday afternoon. There, a gaggle of volunteers bent over voluminous white canvas malt bags from Williamsburg brewery Opa Opa. Large enough for a sack race, the bags are normally thrown out by Opa Opa at the rate of 300 a week, said Cummington artist Leni Fried.

Fried is the founder of BagShare, a program that creates reusable shopping bags out of waste materials. Some BagShare groups gather for sewing circles, making colorful bags out of scraps of waste cloth. Others fold the malt bags into sturdy, double-walled totes. They use grommets – small gold rings – to staple the bags’ corners and attach rope handles to the top.

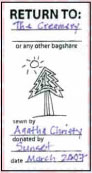

Stores including Serio’s Market in Northampton and the Old Creamery Cooperative in Cummington have “Take a Bag, Leave a Bag” policies where customers can pick up or drop off a BagShare satchel. BagShare volunteers have made over 15,000 bags since the program began in 2007, said Fried. The program, which Fried started in Cummington, has caught on in communities as far away as Australia and Cambodia.

“As an artist, this is something I wanted to share, the creativity and ingenuity and making things as a collaboration,” Fried said. At the Survival Center, the BagShare volunteers were creating bags especially for the nonprofit, which provides low-income residents of the community with food.

Survival Center director Heidi Nortonsmith said she was concerned at first about the nonprofit’s ability to handle the ban. The Center serves 4,700 clients annually, with about 1,000 new recipients each year.

“It’s very difficult for people emotionally and in terms of stigma to come to us,” she said. “We don’t want to put one more thing between them and getting the food they need. To the extent that there’s a hardship, we the center want to absorb that.”

Collaborating with BagShare, Nortonsmith said, will allow the center to comply with the ban without requesting a hardship release from the city.

“With a little extra effort and a little bit of grin-and-make-it-work, we felt we could really embrace the spirit of the ordinance,” she added.

Recycling and reuse may feel like a recent craze. But remaking old materials into new has a long history, points out Steven Johnson in his book on 19th-century London, “The Ghost Map.” There, resourceful individuals salvaged unwanted materials, even finding a use for something as lowly as dog waste – which they sold to tanners who used the material in the leather-curing process.

“Waste recycling is usually assumed to be an invention of the environmental movement, as modern as the blue plastic bags we now fill with detergent bottles and soda cans,” Johnson writes. “But it is an ancient art.”

Meanwhile, here in Northampton the BagShare program – which can be found on Facebook at TheBagShare or at www.thebagshare.org – needs both volunteers and donations. Just one grommet machine costs $250, Fried said. At the Survival Center, I noticed that the single grommet machine limited how fast the volunteers could work. We all lined up behind it to staple our folded bags into totes.

We? Oh yes. I tried it too.

By the end of the afternoon, I proudly had two tote bags dangling off my arm.

“Keep them,” encouraged Fried. As a conversation piece, she said, it might send more people their way. I’ve used them already. They’re spacious and sturdy, light and comfortable to carry. With “Avangard MALZ: Product of Germany” emblazoned on their side in green lettering, they’ve got a fun, upcycled vibe. And as for keeping them? One’s mine, for sure. But I plan to drop off the second one at a Leave a Bag station soon, and join the ancient community of sharing the remade.

Naila Moreira is a writer and poet who often focuses on science, nature and the environment. She teaches science writing at Smith College and is the writer in residence at Forbes Library. She’s on Twitter @nailamoreira.

Serio’s Market in Northampton prepares to stop using paper bags on Earth Day

By BRENDAN DEADY Gazette Contributing Writer

Monday, April 20, 2015

|

| JERREY ROBERTS

- Anya Spector places a customer's groceries into a cloth bag Thursday at Serio's Market in Northampton. |

To prepare for the transition, Serio’s is expanding its involvement with the BagShare Project to have 1,000 reusable bags available at the front of the market at 65 State St. by Wednesday.

BagShare is a program aimed to replace the bulk use of disposable bags by offering cloth alternatives to customers. The project, started in Hampshire County by Leni Fried, uses volunteer sewers to make the cloth bags which are donated to stores.

When a business agrees to host a BagShare station, customers may take one of the bags with the hope that they will return it at their next visit or at any participating BagShare business.

Fried described the sewn bags as a reminder for customers to bring their own reusables as a better alternative to disposables. She added that cooperation from Serio’s customers is pivotal if the program is to make any significant change.

“We as people are so convenience-oriented,” Fried said. “If no one remembers to bring a bag back, then those (1000) will be gone in two weeks. If we as a community want this to work, we need to support Serio’s and we need to change.”

Fried said bag-sharing also brings the community together because each bag is sewn by a volunteer who may add a creative touch. They sew an identification tag into the cloth, a place where Fried said they can write their “name or poetry.”

Serio’s stopped giving plastic bags to customers in 2008 and became a partner with the BagShare Project in 2009.

Owner Gary Golec and general manager Jaimie Golec agreed to give up paper bags when one of their employees Anya Spector approached them with the idea. Spector, a senior at Northampton High, then contacted Fried about aiming to have 1,000 cloth bags ready by Earth Day.

Spector said she offered the idea because the BagShare Project already was in place and she saw an opportunity to make a small difference regarding an issue she cares about.

“I think that a lot of it is getting people thinking about their effects,” Spector said. “Even though it might seem really small at first, it all adds up. It’s a good way to get people into the mind-set to making small sacrifices that are good for the environment.”

Jaimie Golec sat on a milk crate behind the market one day last week and admitted that she and her father have concerns about the transition.

‘Social and economic duty’

“Yeah, we’re nervous, we’re working just to keep the bills and our employees paid. We can’t afford to lose a single customer ... but it’s worth it for the environment, the planet, and as a community-oriented business it’s part of our social and economic duty,” Jaimie Golec said.

Gary Golec, who sat on the tailgate of his red pickup truck, added that even though the independent markets are the ones struggling, they still make the effort to have a positive impact in their community.

“You don’t see the same things happening at chain stores,” Gary Golec said. “Businesses like us, we’re the ones doing things like this. If you like the community you live in, then support the businesses who help your community.”

Jaime said they take every opportunity to use their business as way to make a positive impact in Northampton. They phase out products that have what she described as unethical business practices. They give any local farmers or food companies a chance on their shelves.

Serio’s slogan is “Where friends are customers and customers are friends.”

“Our slogan isn’t just lip service. We really are conscious of the people we see walk in and out of here every day,” Jaimie Golec said.

While the Golecs say they fully support the transition to doing away with disposable bags, Jaimie said they still have to be realistic and accept that some customers are going to want the service they’re used to.

“There’s the reality and the fantasy of it,” Jaimie Golec said. “We can’t afford to refuse a customer a paper bag if they ask for one. We’ll keep a small stock of them but try as much as humanly possible to have customers bring reusables.”

The BagShare Project is important to the Golecs for a more personal reason. Christina A. Cavallari, who owned Serio’s with her husband Gary until she died last May 30, was a passionate supporter of the BagShare Project at the market.

“Like Leni said, there’d be days where we’d host a BagShare sewing and Chris would be the only one out there at the table with a smile on her face sewing away,” said Jaimie Golec, her stepdaughter.

Serio’s is the largest market to make the bag-free switch and the Golecs hope they can be a leader in the initiative. However, they agreed with Fried that they cannot do it alone.

“Our biggest problem is that the bags don’t really get returned,” Jaimie Golec said. “Our customers have been great in showing support but if the bags don’t make it back, they’ll be gone in a week. We can only do 50 percent of the work here. If this is going to work, everyone needs to make a little change.”

Plastic Bag Ban Under Consideration in Massachusetts!

by Juli McDonald, WWLP TV-22 News, Springfield, MA Tuesday, 23 Apr 2013

WEST SPRINGFIELD, Mass. (WWLP) - Paper or plastic? It's a question you might not hear for much longer here in Massachusetts. A growing number of Massachusetts communities have already banned plastic shopping bags, and now some state lawmakers are hoping to enact a single statewide ban. Environmentalists have been hoping for such a restriction; citing the fact that plastic bags don’t easily break down in dumps, and are quick to blow away and become litter.

While many communities across the country already have plastic bag bans in place, if this law passes, Massachusetts would become the first state to ban them at large retail stores.

- Read entire story on WWLP's site here.

- Visit the site of State Rep. Lori Ehrlich, supporter of the plastic bag ban

Need Some Inspiration?

See how to actively support the Plastic Bag Ban Bill and do what you can to see it passed!WHERE IN THE WORLD ARE PLASTIC BAGS BANNED?

Check out the fully interactive map here.

|

| Never Forget All That the Plastic Bag Has Done for Us! |

Bag-Shares Around the World

I recently returned from Nicaragua after spending a week in Amherst’s sister city, La Paz Centro with a group of students and adults. We did various inspiration to do this and carry it to another part of the world. Hope you can open the pictures. The logo on the bag says Barrio Bonito (Beautiful Neighborhood). ~ Nancy

News from the Corporate World

Sometimes it seems like too big a cultural leap to expect customers to bring their own bags, but we're starting to hear more and more stories of retailers - small, big and sometimes GIGANTIC - taking the leap and landing on their feet. Here are some examples:

Costco's Bring Your Own Bag Policy - Besides offering a wide variety of goods, including many whole food items, the (Costco) chain does not give either paper or plastic shopping bags to sack groceries. Customers have to bring these themselves.

Want to Kick the Plastic Habit for Good?

Check out Beth Terry's blog "Plastic Free Guide" with over 100 tips, musings and ideas for cutting plastic out of your life entirely!

And ID tag is sewn on the front of each bag, designating it as a 'Use and Return' bag. The bags are borrowed when someone forgets their own bag and and returned to any BagShare location.

And ID tag is sewn on the front of each bag, designating it as a 'Use and Return' bag. The bags are borrowed when someone forgets their own bag and and returned to any BagShare location.